By Rachel Connolly

The trouble with life is you can only do it once. Choose the creative fulfilment of working as a writer and you likely forgo the financial stability of, say, a lawyer. Decide to have children and you’ll give up some of your independence. Move to an exciting new city and you will discover, after a time, that you’ve left the old one behind. I really wish it wasn’t so, or that I could clone myself and live out multiple realities at once. I love having these decisions, I just don’t want to have to make them.

It could be that possibilities always feel endless when you’re young, but to me it seems that, more than at any other time in history, there are so many different ways we can live. There are so many kinds of jobs, opportunities and incentives to move cities, and ways to keep in touch with the people you meet there and watch their parallel lives unfold.

My fantasy home is technically not a home at all. It would be a deliberately transient place, somewhere that would serve as a base from which I could dip into these different lives. A weekend in Berlin with friends here, two weeks in Derry with my grandma there, a month in London for work. In my fantasy, air travel would be free and carbon neutral. I would live in the Park Hyatt in Tokyo, the hotel which serves as the beautiful backdrop of urban dislocation in the 2003 movie, Lost in Translation.

The Park Hyatt Tokyo is the obvious choice. It is luxurious but understated. The rooms are small enough to encourage my routine of constant travel. There is a pool and a gym on the roof. And the views, the endless stretches of Tokyo skyscrapers: a reminder that the world is so big. I’d be rich enough to order room service whenever I want. It’s my fantasy — why not! And of course, I would speak fluent Japanese.

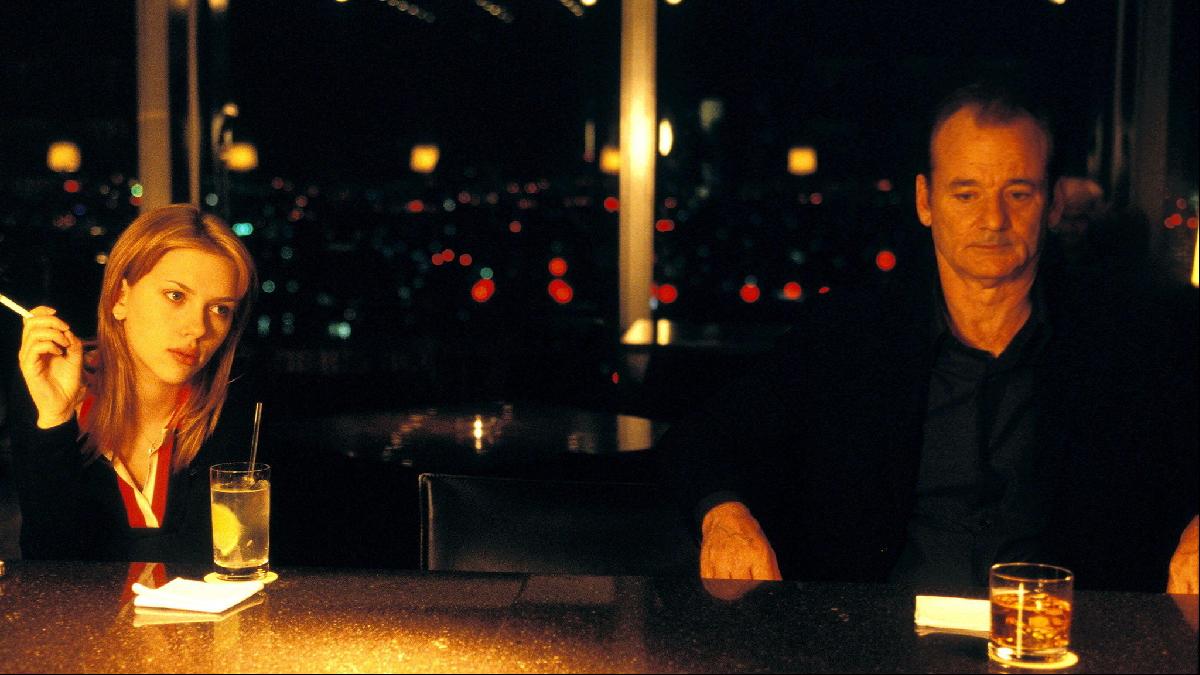

Like so many great films, Lost In Translation requires the suspension of disbelief with some of the finer details. For example, that a woman, Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), who has recently graduated with a degree in philosophy from Yale would have nothing better to do, if she found herself at a loose end in Tokyo, than skulk around aimlessly in frumpy boot cut jeans and sweater vests, listening to audiobooks called A Soul’s Search: Finding Your True Calling. Or that a pink wig donned spontaneously at a karaoke party would remain fixed and perfectly symmetrical, never allowing mousy strands of hair to escape from underneath it. Yet through the relationship between young, lost Charlotte and bored, jaded Bob Harris, played by Bill Murray, the film perfectly captures the human tension between longing for, and then pulling against, fixedness.

Murray portrays the ennui of a middle-aged and past-his-prime actor beautifully. There is nothing wrong with his life. He has been married for 25 years, he loves his kids, he is routinely accosted by adoring fans. He gets paid millions of dollars for a few days work in a whiskey commercial. But, as he says, he does this instead of starring in little plays. He and his wife exchange terse phone calls, trapped in an endless, low level argument about nothing. He is faxed constantly with dreary home decor decisions and posted a box of burgundy carpet samples.

I read this as a comment on how it can feel when your life has set (projecting my own neurosis on to the film, of course); when you’ve picked one of the lives and the other choices have faded away. Because, no matter how much you resist permanence, time does pin you down. But then, it’s my fantasy, so I would never get old.

Photography: Maximum Film/Alamy; Everett Collection Inc/Alamy; Landmark Media/Alamy