By Chris Hayes

The US architect Paul Rudolph began his career at the epicentre of American Modernism, studying at Harvard University under Walter Gropius and other Bauhaus intellectuals who had fled the rise of Fascism in Europe. This formative period in his life was briefly interrupted by the United States’ entry into the Second World War, during which he served in the navy.

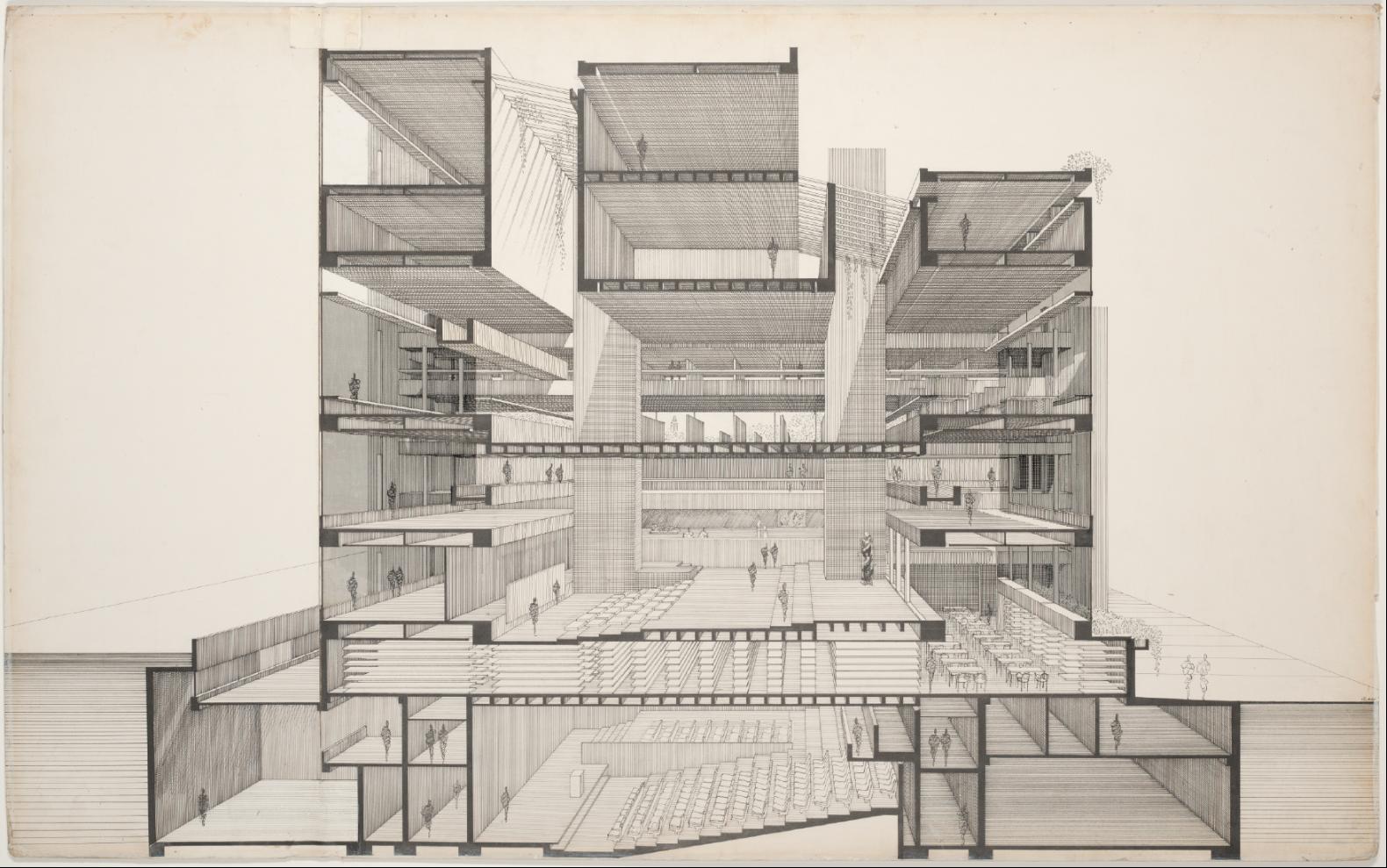

Despite being shaped in such an intellectual hotbed and later holding prestigious teaching roles, Rudolph wrote little throughout his life, preferring instead to let his drawings speak for themselves. A virtuoso draughtsman, he pioneered an idiosyncratic style that featured an x-ray view into the interior of a building — known as a section — where he showed realistic perspective, light and shade, reflecting his belief in the psychological impact of space.

Rudolph is probably best known for his Florida houses, like the Walter Guest House (main image, top). These were forward-looking homes that responded to the local context, defined by low-rise, open-plan structures with ceiling-height windows. Seen at the time as innovative iterations of the International Style, and first constructed as an apprentice of and later partner with Ralph Twitchell, the homes were acclaimed as part of the Sarasota School of Architecture.

Striking out under his own name in 1952, he wandered off the rigid path set by his mentors as his own fame grew through the 1960s. As the head of Yale’s architecture department, he won a commission to construct the university’s Art and Architecture Building, the A & A. Playing the role of both architect and client, he seized the opportunity to create an ambitious, career-defining project — a looming, fortress-like ode to monumentality.

Pairing concrete textured by “bush-hammering” alongside layers of steel-framed glazing, the building introduced elements of ornament into a Modernist design language that had praised functionalism above all else. This shift sparked controversy; British architecture critic Sir Nikolaus Pevsner remarked at the inauguration: “It is all very exciting, a powerful stimulant for the students. May it not be too potent for them; too personal as an ambiance?”

Ever-evolving, Rudolph would continue to reinvent and redefine his relationship to his early influences, working at an ever-larger scale and exploring wider ideas about urbanism. Yet as architectural trends moved away from Modernism, he shifted his focus to Southeast Asia in the 1970s and 80s, where he undertook large-scale commissions in densely packed cities such as Hong Kong, Jakarta and Singapore.

His later-career projects demonstrate a stubborn resistance to the rise of postmodernism. Take the Tuttle Residence, a home completed in 1986, that echoes the style of his pivotal Florida houses with a complex intersection of modular forms, covered in bricks and roofed in copper. An appreciation of scale and context is also present in his fantastical drawings of almost-impossible urban megastructures, which will feature alongside a wider career retrospective in Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph, the first comprehensive exhibition to examine his entire career, running now at New York’s Met Museum until March 16 2025.

One of US Modernism’s most committed disciples, and most consistent defectors, Rudolph believed in urbanism above all else. Writing three years before he died, he stated that it was the defining principle of his practice. Urbanism, he argued, “deals with the old and the new, the expanded and the contracted, the humdrum and the extraordinary. It brings people together. It separates people. It commemorates its history. It never lies, but portrays life three-dimensionally as it really is”.

Photography: Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress; Ezra Stoller/Esto, Yossi Milo Gallery; The Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture